Virtue Ethics Qua Learning Theory

tl;dr – I have converted to virtue ethics because it is tractable and can embed consequentialism and deontology. Moreover, I have realized that ethics is the same as the theory of systems of autonomous learning agents.

Ethics is the study of behavior and its value.

This is very general which partially explains why there are so many wonky theories of morality. Yet in my opinion there often appears to be much consensus on the basics among humans, for example:

However, given we share \(99.9\%\) of our genes [1], maybe this isn’t so surprising.

And “the devil’s usually in the details.” That is, while killing is badong, some consider it okay in self-defense and others don’t. Honesty seems generally touted as virtuous and right behavior but in some cases people might argue that lying is better. Moreover, many humans seem as if they’d have a difficult time with radical honesty. As Ben says, “radical honesty is optimal for optimal people.” So I’d say us humans tend to agree on the basics while vehemently disputing the finer nuances.

When writing a new essay, I like to review my old content on the topic: Dictator Bob’s Valuism, Value Dynamics, and Mythological Memeplectic Morality. The perspective I took was that there are three main ethical questions:

- What is valued?

- How does the world correspond with the values?

- What can I do to live in such a valued world?

Often one talks about whether a certain behavior is right or wrong as if our values are fixed and for every behavior, there will be a crisp yes-or-no answer as to whether it’s good or not. There are a lot of unspoken assumptions here, which, for what it’s worth, are not entirely unfounded given our genetic and cultural affinity. I think it’s important to recognize that an exploration of values is a fundamental part of ethics. According to Wikipedia, this question can be called meta-ethics or axiology: what are values?

And are moral dilemmas just number-crunching once we determine our values?

It’s not clear how values are determined. Humans have diverse preferences, so once we move beyond almost-unanimous topics such as killing, Moral Relativism is alluring: different people can have different values. On the other hand, there seem to be good evolutionary arguments that survival is an inherent value in the Cosmos. The basic idea is that systems that develop the capacity to sustain their existence will continue existing whereas those that don’t will be more likely to cease existing: thus one will expect many systems to implicitly value survival, even if they are not consciously, self-reflectively aware of it. Moreover, living a life according to one’s values may prove difficult if one ceases to exist (or at least one will have trouble verifying the highly valued state of affairs), so survival is at least an inherent instrumental value.

This reminds me of the nature versus nurture debate as to whether (human) behavior is determined by the environment (during development) or by the genes. As with moral relativism and values, people seem to want a clear either-or answer when it appears that none exists. There are tight feedback loops where nature and nurture influence one another and both are at play in many behaviors. Likewise, there are probably more-objective and more-subjective values. Furthermore, once a (human) being develops to a sufficient degree, it may be able to deliberately choose which values to adopt, potentially prioritizing explicit values over implicit values (such as survival).

David Pearce claims that valence is the intrinsic measure of value in the universe. Valence refers to “the intrinsic attractiveness/’good’-ness (positive valence) or averseness/’bad’-ness (negative valence)” of experiences. Joy and pleasure are positive valence. Anger, fear, and sadness are negative valence — they just, like, feel bad, right? Thus, Pearce claims, we always know the value of our own experiences!

Chocolate peanut butter cheesecake is just plain good; however, regular consumption of large quantities appears to lead to health problems and unpleasant, negative valence feelings. Thus we talk about ‘temperance’ being a virtue and ‘greed’ being an immoral vice: we believe they lead to behaviors or habits that will bring about positive or negative valence experiences. The really tricky situations are where we experience a lot of positive valence for a while until eventually a truckload of negative valence catches up with us! Knowing this, one may experience mixed feelings when enjoying a good cheesecake: perhaps valence is multifaceted?

And matters become even loopier when one realizes that the valence associated with an experience can change. Before 2012 I couldn’t stand bananas (🍌). I got really strong gag-reflexes and was utterly repulsed by their taste, smell, and texture. I couldn’t even handle smoothies with bananas in them. Life was difficult. Determining that bananas seem healthy and that I’ll enjoy life more without food dislikes, I sat down with a good show, a chocolate bar, and a banana. I took small bites of the banana with chocolate, slowly acclimating myself to everything about bananas. Two hours later, I was done. Before long, I have come to really love bananas (as evidenced on Instagram). Now bananas are good, largely by my deliberate choice. Is this related to ethics? Well, I think that people would agree it’s pretty bad to force feed bananas to someone who experiences such revulsion at them. Did I commit self-harm during the acclimatization process? Perhaps a bit 🤐. Does this mean it’s morally good to feed myself bananas (in moderation)? I think so, actually. Why don’t we talk about it like this? Probably because it’s kinda boring and we like to talk about the contentious cases 😜.

So even if valence is an intrinsic measure of value in the universe, or just in humans (who are pretty similar to other mammals), this doesn’t tell us why certain experiences (such as eating a banana) feel ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Nor is the relation of an experience to its valence necessarily fixed: the value of bananas for specific people can change. We can learn to like or dislike things. Oh, and maybe bananas are easy because they’re healthy, that is, as with survival, some things may be easier to value than others.

I’ve been studying meta-learning theory lately and it appears to have the same phenomena where the choice of value is a free parameter. The highly esteemed Juergen Schmidhuber along with Tom Schaul beautifully explain the theory of learning and learning to learn if you’re curious ;- ).

In plain English, “learning is changing oneself in such a way that one’s behavior in possible situations is expected to perform better than before.” In other words, learning is the process of acquiring knowledge or skill with experience. Curiously, one can talk about possible experiences instead of possible situations based on the etymology, which was interesting to me. When doing machine learning, the learning algorithm and the applied model are often distinct. That is, I’m running an algorithm that builds models with incrementally better performance. … performance, huh?

What does performance mean? Dr. Schmidhuber says that “a task associates a performance measure \(\phi\) with the agent’s behavior for each experience.” This sounds an awful lot like a moral judgment: artificial intelligence (AI) is about learning to be a good boy 🐶😇.

And as with ethics, learning theory itself is agnostic and says nothing about where the performance measure comes from. For AI, the human plays ‘God‘ and simply tells the learning algorithm what is ‘good’ and what is ‘bad. For what it’s worth, humans are prone to telling each other what to value as well, but that often pisses off other humans who reserve the right to say, “bugger off!”

The learning setup is that there’s a world of possible experiences, a set of training experiences (in memory), an agent (such as a human), and a performance measure (aka a set of values). Then one wants to find a learning algorithm that, based on the known experiences, changes the agent so that we expect the agent to be judged better by the performance measure. And we somehow want to estimate this expectation over all possible experiences even though we may not know them all. This may sound a bit far-fetched and it is!

“Perfect learning” seems to be impossible: there is no free lunch. Mathematically, there is a way to complete inductive learning called Solomonoff Induction. Inductive learning is learning by experience and applying this to predict the future (or generally speaking, new experiences). The classic example is, “the sun has risen every day so far, thus it’s reasonable to predict it will rise tomorrow, too!” The idea of Solomonoff Induction is to find all computable theories that perfectly describe all training experience. We want to use these to calculate the likelihood of future experiences. There’s a principle called Occam’s Razor that says, “the simplest explanation is usually the best one”, or in learning, “the simplest explanation is the most likely to generalize to new data.” So we weigh short theories more than long theories when combining them all to estimate what’s next. The philosophical principle is pretty simple — yay? Well, the method isn’t computable by any machine. That didn’t stop Marcus Hutter from trying to develop a universally optimal reinforcement learning agent, AIXI, based on Solomonoff Induction; however, in 2015, Hutter showed that these optimality results are undermined because any agent’s policy can in a sense be considered Pareto optimal over all computable environments. (By the way, my brother Qorxi’s name is inspired by AIXI. Quantum Organized Rational eXistent Intelligence.)

There are some interesting and important differences between this learning setup and humans. First, human values are part of us: the performance measure is part of the agent. People teach us new tasks via external validation and then we can learn the performance measure as we internalize it and master the new task. There is some research on reinforcement learning systems that learn the utility function (performance measure) that investigates whether the agent will wirehead (which is deciding to always be happy no matter what happens). Second, humans can be open-ended and flirt with many tasks throughout their lives (‘defined by’ performance measures). Humans learn how to learn (meta-learning) and humans learn how to choose what to learn. And as in my case, humans can, based on their current value systems, choose to alter their own value systems. There’s the field of moral development focusing on how humans learn “how to behave” and “how to relate to their values.” I suppose writing this essay is part of my moral development. Tehehe 🤭😋

However, I’d say these differences are a deficit in how “learning theory” for “artificial intelligence” is currently being framed. Most focus seems to be on point 3 of ethics, learning “how we can do better”. The concept of a performance measure combines both points 1 and 2: it tells us what is good and how to determine the goodness of an experience. I think there is value in distinguishing them, especially when self-reflexively exploring one’s own values. Learning theory will be more comprehensive when it includes point 1, “what is good?”.

When this is recognized, one sees that the theory of learning in autonomous systems is more-or-less the same as the theory of ethics, just from a different perspective. Moreover, the field of decision theory is pretty much the name for point 3 of ethics, which also corresponds with applied ethics and normative ethics. The theory of ethics is very grounded in millennia of human experience and wisdom related to real-world situations that humans face. And we tend to assume that there is a lot of overlap of values among humans, even positing that some are universal properties of life in the cosmos. Whereas the performance measure is so isolated from the AI system in meanstream culture that we talk about “super intelligent paperclip maximizers on the loose“! Perhaps this is just the AI equivalent of didactic stories for children’s moral education.

Learning theory can help us to see why ethics and moral theory is so darned difficult and confusing. Ultimately, we seek moral guidance as to how to take right action in, well, every single situation we will ever find ourselves in. And we seem to judge and censure ourselves when we realize we’ve taken wrong, harmful action. But we also know that it’s theoretically impossible to act optimally in every situation given non-trivial performance measures (values). Moreover, Correy Kowall pointed out to me that No Free Lunch theorems imply that no matter how good you think your moral rule is, there exists a scenario that gets you to act in a way that is bad by your own standards. This should probably influence how we approach ethical thought. For starters, forgiveness seems encouraged when perfection is unavailable. To cite Correy Kowall again,

Imperfect + willingness to change = perfect enough

So ethics, the study of right action, is pretty insoluble on the personal level. Aaaaaaaand humans usually live in multi-agent systems called societies. Romantic relationships among two humans already provide so many challenging situations that inspire numerous books to be written! We each have our own values and even where they overlap, as we both enjoy each other’s company, we have different preferences as to how to spend time together, how often, how long, et cetera. There are so many ways for the state-of-affairs to deviate from one or both partners’ desired zones. We can empathize with each other and learn to model each other’s values. This helps with learning to harmonize our behavior so that we both joyously approve. What happens if we break up and I meet a new partner? And this happens a few times? Do we start from scratch in learning how to cooperate for the mutual fulfillment of our values? No! We learn from the commonalities among our partners how to cooperate (with humans) in general. For example, we learn to make time to talk about concerns and situations where our values are not being satisfied. And then as there are more people in the society, more communication may be needed to help everyone live together with values satisfied. Ethics tends to concern itself with how to help people behave harmoniously in larger tribes and communities.

There are three primary paradigms in the field of normative ethics on how to determine “right action” based on one’s values:

- Consequentialism determines right action by measuring the net benefit of the action’s consequences. Utilitarianism is the most well-known form of consequentialism that suggests the most right actions maximize happiness and well-being in the cosmos.

- Deontological Ethics aims to codify right and wrong action according to a set of rules or duties, such as Kant‘s famous categorical imperative, “Act only according to that maxim by which you can also will that it would become a universal law.”

- Virtue Ethics focuses on traits or qualities that are deemed to be good. For example, acting with courage, truthfulness, and kindness is regarded as virtuous and right action, even if the consequences appear harmful.

All of these paradigms clearly have their own rationality to them as well as strengths and weaknesses.

Consequentialism is very easy to think about and relate to decision and learning theory: you take some measures of well-being and crunch the numbers to figure out the best actions. On the personal level, people can use Pro and Con lists (apparently also called decisional balance sheets) to make choices. I did this before drinking coffee. I was concerned about becoming addicted with a physiological dependence; however, I concluded the benefits of assisting me to stay up late and being able to enjoy good coffee regularly outweighed the need to regularly spend money on caffeine.

The ambiguity is clear: how do I compare the pros and cons? Is physiological dependence better or worse than the help to stay up late? We quickly run into meta-ethical questions about what values are, how their satisfaction or violation can be judged, and how they can be compared. Can I assign numbers to them so that, say, utility(staying up late) = 9 and utility(physiological dependence) = -5? Sure but is there some systematic way to do this or does it just depend on my mood? Can I rely on the intrinsic value of the experiences a la David Pearce’s views? To do this I will need to try coffee out and observe how I feel on the drug. I may want to try quitting coffee a few times to measure the withdrawal effects. Now that I know what it’s like, perhaps I can ‘just know‘? Except comparing the positive and negative valence also seems unclear. Not to mention my experience of withdrawing from caffeine might be different each time (as Heraclitus reminds us, “you can never step in the same river twice”). Some values, “such as liberty and equality, are sometimes said to be incommensurable in the sense that their value cannot be reduced to a common measure.” Thus it may be wrong to expect that we can even compare all pros and cons! However, if we can figure out how to compare all the different options, then there are theorems asserting we can assign values to them in a consistent manner [W].

The next challenge is that even if we manage to assign values to all experiences of all members of society, the actual optimization problem may be intractable. This attitude resembles a top-down planned economy, actually: allow the algorithms and their maths to compute the optimal economic actions for every citizen. The 🦋 effect makes matters even more fun: in chaotic systems a small change can lead to a large difference down the road. So we probably can’t foresee all the consequences of our actions when making choices. Consider the Haber process, which takes nitrogen from the air and fixes it into ammonia for fertilizer. It is widely used all over the globe today. However, Fritz Haber barely lived beyond the receipt of his Nobel prize. So he could not have been truly aware of the benefit of his own actions. Curiously, this might imply that consequentialism is more useful for ethical accounting after the fact. Then we can learn what actions were truly beneficial for reference going forward. Hail wisdom 🥳

We can use the consequentialist ideas to guide our actions even if it’s not possible to find the truly best option. Maybe we can compare some factors but not others and find an estimate as to what the consequences will be. We can remain open to learning as we try our best.

Deontological approaches appear on the surface to be much cleaner to deal with than consequentialism. The idea is to come up with rules to follow to behave right, such as, “killing is badong.” Another rule might be that “every human has the liberty to do whatever it wants with its body so long as it does not harm another.” Where do these rules come from? The divine command theory proposes that God tells us the rules to follow and, erm, that’s that. It’s pretty simple and solid if you trust your divine sources. Otherwise, wise humans propose the rules and we collectively accept them or not. They are often codified into our legal systems and constitutions. This is a huge advantage to deontological approaches to ethics: declarative knowledge is very easy to share.

My previous essay, Dictator Bob’s Valuism, is closer to utilitarianism because I wrote things down in a formula suggesting numeric measurements. Thus I might be inclined to posit that we ground ethical rules in consequentialist analysis. Killing is badong because it almost always seems to lead to more misery than joy. This also explains why there are more nuanced guidelines such as, “killing is permissible if it is in self-defense and even noble if it is to protect others.” So killing a terrorist to save a few thousand people is virtuous, right behavior.

One might want to go a step further and attempt to do a mathematical proof that one’s law will be better than doing anything else. Maybe within some models of agents in a society, one can prove that this rule leads to optimally harmonious behavior and any violations of it are inferior. However, to do this, one needs a way of determining which actions are good or bad. So one’s assumptions would have to be moral rules themselves. Perhaps one could start with moral tautologies by asking, say, what’s the ethical equivalent of “A = A”? This seems to be what Kant aimed for. He defined “good will” as “acting out of respect for the moral law”. What is the moral law? Well, it’s being defined here as acting in good will! The categorical imperative that “one acts only by a maxim one wills would be a universal law”, indeed resembles a mathematical axiom. Something like, \(A \to \forall_{humans} A\), “if I do A, then I will all humans do A”. As with axioms in mathematics, there’s no fundamental theoretical justification for the axiom. There is a field of reverse mathematics that seeks to determine which axioms are needed to prove theorems, so we could ask which axioms of the Kantian variety are needed to prove that “killing is badong”. The rules mentioned so far are not sufficient. I would seem to run the risk of getting killed if I kill and will that everyone kills, but there is no axiom that says this is a “bad outcome”. Nor does it say when everyone will kill nor that they will not share kills, so the system doesn’t “necessarily self-destruct”. While mathematical axioms are semi-freely chosen by us humans, they tend to be very simple compared to the theorems we prove with them. Thus it could be easier to collectively agree on the truth of the axioms and then prove a profound result from them than to collectively agree on the truth of the result. So this program of deontology might be worthwhile when it is capable of producing ethical theorems.

Alas, the rules are plain and simply not grounded in anything more than consensus. Choosing to ground rules in proofs from a system of consensus axioms is fine as is choosing to ground rules in consequentialist estimates. When we do agree on rules such as, “killing is badong”, they do help to greatly simplify discourse. We don’t need to recourse to careful utilitarian calculations to realize that not-killing is good, right, and gnodab. The rule says so. This might suggest that deontology and consequentialism can be productively combined: first try a tried rule according to grandma’s wisdom and if none apply, then recourse to estimating the values of the consequences of every viable option.

The other problem with all these rules is that they can conflict with each other. Bodily autonomy and not killing are confounded by the dilemma of abortion: does the mother’s right to her own body outweigh the life of a fetus? One rule says go for it if you want to, girl! The other rule says, no! Or maybe before a certain age, the fetus isn’t human and thus it’s not truly the badong kind of killing. Thresholds like these tend to be fuzzy, so we won’t get a clear-cut answer and will likely have to make heuristic judgments of the utilitarian variety. Or, frankly, as we’re free beings, we can resolve the conflict however we want. The justifications are just to help guide our decisions and to help achieve consensus.

While both deontology and consequentialism focus a lot on the actions one takes, Virtue Ethics focuses on the character of the person taking actions. If I am virtuous, then the actions I take will be virtuous.

The idea is that courageous people will take action where beneficial even in the face of fear and it is also emphasized that recklessness will tend to lead to harm, which distinguishes courage from fearlessness. An honest person will generally speak the truth without succumbing to the temptation to micromanage an assortment of (white) lies aiming for higher utility. A just person will seek out win-win situations and will be reluctant to receive boon at someone else’s expense. A superb virtue is phronesis (prudence or practical wisdom): good judgment in determining how to act and what is needed for a good life (eudaimonia). Apparently, Socrates claimed that the only fundamental virtue is knowledge and that the rest will follow. You can consult some lists on Wikipedia here and here. According to Alasdair MacIntyre in After Virtue, Aristotle claimed one needs to possess all of the primary virtues to be truly virtuous of character as they mutually support each other.

There is no claim that a virtuous person will obtain the best possible result as is the goal in consequentialism (despite the fact that in practice one must satisfice). Nor are there hard-and-fast rules that, say, a truthful person must literally always say the truth as there may be under deontology. Being able to practically cope with the fuzzy edge cases and difficult situations is itself a virtue to be developed!

Virtue ethics is a decentralized protocol that works best when everyone is on the same page. When most beings in a society agree on the virtuous character traits and can trust every member is trying to live by them, then the hypothesis is that on the whole the values of members in this society will be more ongoingly fulfilled. And in the Western culture I’m familiar with, creativity, diversity, and independence of thought are all valued, which may serve to counterbalance a tendency toward a homogeneous society where everyone agrees on everything. I’d postulate along with Logan that a good top-level value for society is diversity of phenomenological experience.

An important concept mentioned in After Virtue is that virtues as character traits need to align with what one truly wants to do. That is, I am not honest because I believe that “a good person must be honest” but because I authentically, plain and simply want to tell the truth. Thus once a virtue is sculpted into one’s character, it’s low-maintenance. This serves to distinguish virtues from rules.

My stance is that all three of these paradigms have their perks and it’s misguided to expect one to be superior in all situations.

How might this look from the computational perspective? Sometimes one can clearly specify a problem and solution with rules and programmatic precision, such as exact algorithms for sorting numbers (e.g., \(\{2,3,1\} \mapsto \{1,2,3\}\)). Watching sorting algorithms at play can be quite fun and illustrative. There’s no need for a consequentialist specification of the highest good where each action is judged according to how it contributes to sorting the list. The virtue of modesty and humility may apply here: each number \(x\) should know its place without trying to place itself above a number it’s not (imagine \(3\) getting cocky and thinking it’s bigger than \(666\)!) and without believing itself to be less than it is. Thus the numbers, when virtuous, will sort themselves without recourse to rules or calculating the consequences of each re-arrangement. In this toy example, all paradigms can work albeit in rather different ways.

What about a more complex domain such as Autonomous Weapon Systems? There’s the basic maxim: “do not kill.” It may be fairly non-trivial to get military robots to operate with non-lethal means only, actually. However, slaughterbots are meant to operate in the gray zone where we wise humans have deemed there to be a just exception to the maxim. Deontologically, I suppose the rule would need to be extended: “do not kill unless this rule is superseded by a higher priority rule.” One such rule is the principle of distinction stating that the robot needs to distinguish combatants from non-combatants. In practice, recourse is made to consequentialism with the principle of proportionality requiring civilian damage to be proportional to the military aim. This resembles the principle of tit-for-tat, which covers self-defense: it is okay to cause harm if it prevents at least as much harm from being done. How does one actually implement these goals in practice? It seems difficult enough for a human. Moreover, we can’t forecast the consequences of military action with high precision, let alone when on a battlefield and needing to make split-second decisions. This situation leads Karabo Maiyane to suggest that the robots may need to learn to be virtuous by experience as killer robots exist on the edge cases of deontology and beyond the capacity of number-crunching consequentialism. This sounds like a reinforcement learning domain where the agent needs to learn to respond satisfactorily in diverse environments we don’t have clear specifications for (or, as in the case of Go, can’t solve directly). Moreover, we definitely want the robots to be continuously cultivating their character as they act in the field. It may be desirable that the robots develop a capacity for empathy and compassion, which could serve as a strong bias against needless slaughter. The fear with reinforcement learning based approaches is that it comes with very few guarantees as to the robot’s behavior, especially in unexpected situations. In the case of autonomous weapon systems, all three ethical paradigms kinda fail. Is this a domain without foolproof strategies? Please correct me if I’m wrong but we’re not even clear what we want in this domain: “do no harm” and “protect people and robots from harm even if lethal force is necessary” clearly contradict. Everyone chooses how to balance these two values in their own way and we humans can only do our best, just like the cute slaughterbots.

Recognizing that ethics and learning theory are two lenses on the same object serves to make clear that there are no magic bullets that offer perfect guidance in all environments. Moreover, ethics is not a special field that is separate from the rest of life. This points in the direction of embracing a pragmatic ethical attitude of appreciating what each ethical paradigm has to offer.

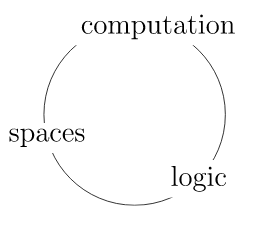

I see a loose analogy with the computational trilogy:

There are equivalences between programming and logic (as well as with category theoretical spaces), which allow one to ground the foundation of mathematics in either framework as well as to choose the appropriate perspective for a given situation.

This begs the question: do the primary ethical paradigms subsume each other? I believe the answer is, yes!

Martha Nussbaum notes that philosophical proponents of the deontology and utilitarianism persuasions often reference the virtues and moral development. So it would seem I’m not alone in this judgment.

One connection comes when one asks what truly matters from a consequentialist point of view: maximum happiness, right? But what is happiness? The best conception of Heaven I’ve seen amounts to: “Heaven is what it’s like to live as a Saint.” I believe this more-or-less corresponds to a Buddhist understanding. And what is a Saint but one possessed of great virtue? The argument is that cultivating virtues leads to one’s lived subjective experience being more pleasurable, less painful, and overall higher valence. Thus cultivating the virtues is to be encouraged from a consequentialist point of view! The dark side is that helping a virtuous person is likely more ethical than helping someone suffering from depression, that is, unless you can cure them of depression. Moreover, a consequentialist may view cultivating autonomous virtuous agents as one means to encouraging overall beneficial actions. Consequentialism gladly gobbles up any effective strategy.

So as discussed with sorting, when there are clear right actions, a consequentialist response can be to simply adopt the deontological rules and move on. Burning energy and time doing things inefficiently is probably low-key unethical as that doesn’t seem like a very good process-outcome! And actually, when there are limited resources, one has to act based on heuristics, so going by deontological rules of thumb might often pay off (rather than trying to reinvent the wheel every time in search of slightly better performance).

A deontological rule to encompass consequentialism may also be pretty simple, e.g.: “to the best of your knowledge and capacity, always act for the maximum benefit of all present and future sentient beings” (CZAR #1). What about a simple rule such as, “be virtuous”, along with a clear description of the sanctified virtues? The pragmatic challenges of deontology are glaringly apparent but it can easily subsume the other paradigms. This is similar to the challenges posed by logic programming: concise specifications are not correlated with effective implementations.

There’s a really clean hack to embed consequentialism into virtue ethics: adapting to evidence of harm with care is a virtue. This basically follows from learning or phronesis plus compassion. Thus a virtuous person, going with a standard set of virtues, will behave in line with consequentialist ethical judgments, too.

To embed deontology, consider the virtue of acting in accordance with one’s best beliefs and declarative knowledge as to how to be good. In two words: rationality and integrity. Such a virtuous being will follow the best deontological rules its culture has cultivated.

Virtues seem very similar to deontological rules; perhaps I could call them embodied rules that have been thoroughly integrated into the very fabric of one’s being. Formal descriptions of honesty and “don’t lie” are similar but the virtue is fuzzy and acknowledges edge cases, which makes the descriptions more concise (as clearly listing all possible edge cases is not tractable).

Another interesting virtue/rule might be: adopt others’ values as my own. Being a ‘good person’ essentially amounts to helping others get their needs and desires met, right? This is a form of nonduality and may lead to many virtues and behavior that overlaps with utilitarian behavior. To make matters more fun, even delayed gratification follows from this virtue because it involves adopting the values of my future self as my own (my present self’s). The question of how to prioritize one’s myriad values remains.

As an aside, I previously discussed how Compassion and Power Ethics both lead to the same sorts of behavior or ethical policies. Whether “good or evil”, if one lives in a society, one will likely want principles of reciprocity that lead to treating each other with deference and cooperating in the fulfillment of each other’s values. While the classic puzzle, the prisoner’s dilemma, demonstrates how selfish/evil beings will fuck each other over, in the case where one plays over and over again, cooperation is the theoretical correct choice. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend exploring this interactive introduction to The Evolution of Trust in game theory that explores some of these dynamics. Thus even if values can be relative and some beings plain and simply don’t care about others, the actual ethical suggestions may vary less. Rather intriguing.

This reflects one of the basic laws of human stupidity: evil bandits are less harmful than stupid people. Why? For bandits will “act rationally for their personal gain” and tend to gain at least as much personally as they cause harm (or so Carlo Cipolla stipulates). Stupid people, on the other hand, will screw things up and cause harm even when it doesn’t benefit them much. Evil beings will by-and-large cooperate and good beings, valuing the evil beings’ values, will also be happy to cooperate with some caution not to be preyed upon.

The big question is, in Ben’s terms, whether goodness is more efficient than evilness. Can we set up archetypal examples like the prisoner’s dilemma where better performance is available (even individually) to a group of good beings? One reason may be that if I only want to perform the best, I might share misleading information with others. Trying to handle #fakenews probably makes good performance more difficult for most players. More synergistic cooperation will be possible when I am willing to share information that benefits you more than me. My hunch is that these effects may accrue over a long time horizon even more than in short-term scenarios one can ‘game’. I suspect a high-trust, transparent society will be fundamentally far more effective than one with constant friction as we try to safeguard ourselves in numerous ways. If you are aware of work answering these questions, please let me know ;- ).

Of the trinity, I currently find Virtue Ethics to more cleanly and flexibly embed the other strategies. I recommend using it as the base framework from which to apply the others.

I personally found my way to virtue ethics by way of universal intelligence measures! They’re like generalizations of IQ tests, which aim to measure a person’s cognitive capacity based on giving them a few puzzles. The idea is that one’s ability to identify and work with patterns on a good sample of puzzles will reflect one’s general intelligence as applied in real life. They apparently have a dark history and it’s debate how effective the tests are. What if some cultures value certain types of smarts more than others and they create the IQ tests that they then judge the other culture’s members by? Would this mean that each culture can have its own IQ test with abstract puzzles representing skills they personally value? That might make sense.

Anyhow, the idea by Shane Legg and Marcus Hutter is to measure the performance of an agent in every single computable reward-summable environment and then to add them, weighing simple environments more than complex environments as in Solomonoff Induction. This isn’t even anthropocentric, though bias can enter in the choice of the (universal turning) machine used to judge the simplicity of environments. IQ tests are clearly one approximation to the universal intelligence test. And as universal intelligence clearly can’t be measured, we have to approximate it by sampling environments according to some schema.

I find it a bit odd that solving problems in real life counts for less than solving an abstract version on paper. I personally am better at solving problems intellectually than in practice but the real world is a more complex environment! But mathematically, this property is needed or else the summation will explode! I like how the definition of universal intelligence easily includes emotional and social intelligence as well as standard IQ tests, however: clearly social intelligence should allow one to perform better in many environments.

So where do virtues come in? A virtue is a trait of an agent that is expected to increase (universal) intelligence over a collection of environments that one values. Performing well over all possible environments runs into weird challenges, as seen with AIXI. One core issue is that one can set up all sorts of crazy heaven and hell worlds that would require very different strategies — but the human world on Earth is neither a hell nor a paradisaical heaven (yet). Cutthroat virtues in a hellish dystopia may actually be rather dysfunctional in a eutopian safe haven and vice versa. Thus virtues can be seen to be objectively relative to the environments where one wants to perform well (as well to one’s values by which performance is measured). The virtues of consequentialism, deontology, caring for others, and many standard ones likely fit this conception.

I hope with my newfound clarity I can engage in discussions and explorations of ethical questions with less conceptual friction. Remember, my friends, the co-evolution of virtue and value with experience is one of the interesting parts!